Overview

As the climate that Darwin’s finches have adapted to rapidly changes, they face a new type of evolutionary test. Now faced with the risks associated with climate change such as increased frequency of El Niño events that encourage invasive parasitic flies population growth and bring torrential rainstorms that wipe out habitat areas, the Finches must adapt or go extinct. As an endemic island species that inspired the theory of evolution which changed the scientific community forever, Darwin’s finches hold a biological significance as well as a social one. The adaptive radiation demonstrated by Darwin’s finches showcases the breadth and depth of evolution and gave the world the blueprints for natural selection. As the climate continues to change, all fourteen of Darwin’s iconic species will be faced with the challenge to adapt as quickly as the climate warms or go extinct. The vulnerability of the island finches is stressed by human influences on their environment. The extinction of a species known to adapt may be a wake-up call that our climate is changing more quickly than anything can keep up to.

Hazards, Vulnerabilities, and Exposures

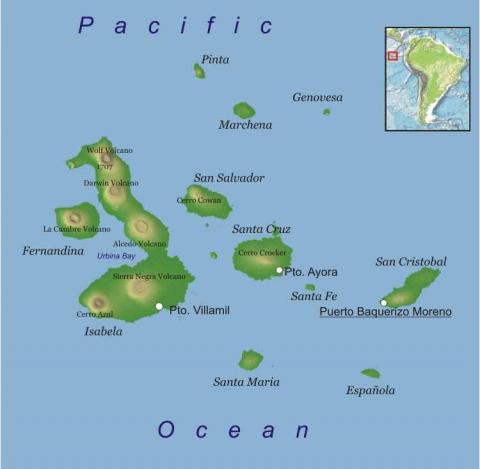

The Galapagos Islands face an assortment of climate change risks and impacts associated with increased precipitation, warmer ocean waters, and temperature variation due to its geographical location at the center of four major ocean currents in the Pacific Ocean (Ecuador 2017, Karnauskas 2015, Adapting).

Hazards

- Air Temperature Increase; The Equator is expected to warm by 2 degrees Celsius (IPCC, 2018)

- Sea Temperature Increase; Warmer waters have fewer nutrients, are less productive, and have the potential to collapse the entire marine food web (Medland 2014)

- Increased Rainfall; Warmer air and sea surface temperatures will increase evaporation and thus rainfall on the islands (Medland 2014, Solomon 2017)

- Sea Level Rise; Will reduce shoreline habitats for marine species (Medland 2014)

- Ocean Acidification; Corals could disappear from the Galapagos by 2100 (Medland 2014)

El Nino Events

-

The El Niño events of 1982-1983 and 1997-1998 demonstrated the exposure and vulnerability of the country’s key economic sectors and biodiversity to climate change (Ecuador 2017).

- The El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is predicted to increase in frequency and intensity due to anthropogenic climate change (Holmgreen 2001, Karnauskas 2015). The warmer waters that define El Niño events also warm the atmosphere above the Galápagos and increase precipitation in the forests (Smith 2015). During El Niño years, rainfall is estimated to be four to ten times higher than island averages (Holmgren 2001). The increase in precipitation due to climatic changes has devastating cascading impacts on Darwin’s finch population as invasive species thrive and habitats are lost (Pimm, Solomon 2017, Galapagos 2018).

Invasive Species

Introduced species are often able to thrive in shifting environments because they are more resilient than native species. Although climate change does not contribute to introducing invasive species, the ones already present in the Galápagos are expected to benefit from increased rainfall brought by El Niño events (G. 2018, Holmgreen 2001, Solomon 2017).

- Philornis downsi, a common housefly prays on finch nestlings by feeding on their blood while they are too young to leave their nests (Pimm). As climate change continues to increase annual precipitation on the islands, the P. downsi fly population flourishes (Solomon 2017). In 2013, over one-third of finch nestlings died from the parasitism of P. downsi flies (Pimm). In some years, entire nestling populations die when they are parasitized (Pimm).

- The Mangrove Finch, one of Darwin’s initial species identified on the islands, are critically endangered due to the threat posed by these flies (G. 2018). The Mangrove Finch is the most habitat specific of Darwin’s original finches identified and can only be found on two of the Galápagos islands, Isabela and Fernandina (G. 2018). The Mangrove Finch is of utmost concern due to this limited endemic range and holds a unique status as the most endangered bird in the Galápagos as only 100 individuals remain (G. 2018).

Habitat Loss due to Invasive Species

- Since the Galápagos Islands discovery in the early 1500s, human settlements have introduced a variety of non-native species to the ecosystems (Solomon 2017).

- The introduction of the non-native blackberry bush wreaks havoc on the habitat of finches across the island archipelago. Finches nest in mature Scalesia trees while seedlings lay dormant on the forest floor to provide the next successive generation (G. 2014). Where the blackberries have invaded the forest, they smother the Scalesia seedlings and prevent them from ever reaching maturity (G. 2014). When El Niño events decimate the existing Scalesia tree forests, there is no second generation of seedlings to take their place (Solomon 2017).

- This is a two-fold threat to the Scalesia forests that ultimately further reduce the habitat of the finches on the island and adversely affect the next generation of finches (D'Ozouville 2010).

- Non-native plant species are able to adapt to variation and climatic changes because they have not been evolutionarily adapted to the specific climate. This puts the Scalesia trees at a severe disadvantage as the tree species may not be able to withstand the changing climate in the Galápagos. As the Scalesia tree forests slowly disappear, so do the nests of Finches.

Adaptation and Resilience

Several species of Darwin's Finches have begun to respond to threats of climate change through human intervention and behavioral adaptation

Species Adaptation

Darwin’s finches have been observed rubbing their feathers on the Psidium galapageium tree as a natural repellent of P. downsi (Cimadom 2016). Experimental evidence shows that P. galapageium leaf extract is an effective repellant of ectoparasites that prevents larvae growth (Cimadom 2016).

International Adaptation

- A majority of the fifteen hundred introduced species to the Galápagos do not wreak havoc but the select few that do cause enough catastrophic damage that the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization added the Galápagos Islands to the World’s Heritage site list to preserve and protect them from invasive species in 2007 (Solomon 2017).

National Adaptation

- Through the “Green Climate Fund Readiness and Preparatory Support for National Adaptation Plan in Ecuador” project, the Government of Ecuador is working to develop a National Adaptation Plan (NAP) to reduce vulnerability to the impacts of climate change, build adaptive capacity in prioritized sectors, and facilitate the coherent integration of climate change adaptation into development planning processes, policies and strategies related to food sovereignty, agriculture, aquaculture and fisheries; productive and strategic sectors; health; water patrimony; natural heritage; and human settlements (Ecuador 2017)

Conservation Efforts

- A recent experiment in the Galapagos centered around the parasitic flies P. Downsi flies has shown promising results in limiting the destruction of finch fledglings (Knutie 2014, Pimm, D'Ozouville 2010). Mathematical simulations report that P. Downsi flies have the potential to drive finch populations to extinction entirely (U. 2015).

- The same models show that a reduction in P. Downsi fly populations would alleviate this risk (U. 2015). In light of the growing parasite population due to increased El Niño events, a 2013 experiment was performed in which a bird feeder of permethrin-treated cotton balls was hung near finch nests (Pimm, Knutie 2014). The results of the experiment showed promising hope for finch populations; 62% of nests with more than one gram of permethrin-treated cotton had virtually no parasites (Pimm, Knutie 2014). The applied insecticide to cotton balls shows potential to combat the effects of parasitic flies on finch populations to increase their resilience to climate impacts.

Conclusion

As the climate that Darwin’s finches have adapted to rapidly changes, they face a new type of evolutionary test. Now faced with parasitic flies invading nests, torrential rainstorms that wipe out habitat areas, and increased El Niño events, the Finches must adapt or go extinct. As an endemic island species that inspired the theory of evolution, Darwin’s finches hold a biological significance as well as a social one. The adaptive radiation demonstrated by Darwin’s finches showcases the breadth and depth of evolution and gave the world the blueprints for natural selection. As the climate continues to rapidly change, all fourteen of Darwin’s iconic species will be faced with the challenge to adapt as quickly as the climate warms or go extinct. The vulnerability of the island finches is stressed by human influences on their endemic environment. The extinction of a species known to adapt may be the wake-up call that our climate is changing more rapidly than anything can keep up with.

About the Author

Alyssa Watson graduated from St. Lawrence University in 2021 with a bachelor of arts in Environmental Studies and a minor in Biology. She researched the impacts of climate change on Darwin's Finches in the Galapagos for Dr. Jon Rosales "Adapting to Climate Change" in the Spring of 2019 to connect her interests in evolution to climate adaptation.

Citations

Adapting to Climate Change in the Galapagos Islands. (n.d.). Conversation International.

Cimadom, A. (2016). Darwin’s finches treat their feathers with a natural repellent. Scientific Reports,6.

Climate Change; Discovering Galapagos. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.discoveringgalapagos.org.uk/discover/geographical- processes/weather-climate/climate-change/

D'Ozouville, N., Di Carlo, G., Ortiz, F., & De Koning, F. (2009-2010). Galapagos in the face of climate change: Considerations for biodiversity and associated human well-being. Galapagos Report. Retrieved from https://www.galapagos.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/biodiv3-face-of-climate-change.pdf.

Ecuador; UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME. (2017, April 10). Retrieved from https://www.adaptation-undp.org/explore/south-america/ecuador

Feher, D. (n.d.). Galapagos Map[Photograph]. Map of Galapagos Islands.

Fourth National Climate Assessment. (2018). US Global Change Research Program.

G. (2014, August 27). The giant daisy forests of Galapagos. Retrieved from https://galapagosconservation.org.uk/the-giant-daisy-forests-of-galapagos/

G. (2018). Mangrove Finch. Retrieved from https://galapagosconservation.org.uk/wildlife/mangrove-finch

H. (2008, August). Scalesia pedunculata[Photograph]. Santa Cruz, Galapagos.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scalesia_pedunculata.jpg

Holmgreen, M., Scheffer, M., Ezcurra, E., Gutiérrez, J. R., & Mohren, G. M. (2001, February). El Niño effects on the dynamics of terrestrial ecosystems. TRENDS in Ecology & Evolution, 16(02).

Karnauskas, K. (2015, December 01). El Nino and The Galapagos. Retrieved April 13, 2019, from https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/el-niño-and-galápagos

Knutie, S., McNew, S., Bartlow, A., Vargas, D., & Clayton, D. (2014, May). Darwin’s finches combat introduced nest parasites with fumigated cotton. Retrieved from https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(14)00350-9

[Species Adaptation Banner] Merlen, G. (n.d.). Scalesia trees, Santa Cruz[Photograph]. Galapagos Conservation Trust, Santa Cruz, Galapagos, Ecuador.

Padgett, B. (2008, February 4). House Finch Nest and Eggs[Photograph]. Flickr.

Pimm, S. (n.d.). Saving a Darwin’s Finch from Extinction. National Geographic.

Sato, A., Techie, H., O'hUigin, C., Grant, P. R., Grant, B. R., & Klien, J. (march 2001). On the Origins of Darwin's Finches. Molecular Biology and Evolution,18(3), 299-311.

Smith, J. (2015, March 12). Galapagos Ocean Currents Yield Living Aquariaum Rich in Marine Life. Retrieved from https://www.livingoceansfoundation.org/galapagos-currents/

Solomon, C., & Scholl, M. C. (2017, May 25). A Warming Planet Jolts the Iconic Creatures of the Galápagos. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2017/06/galapagos-climate-change-impacts-iconic-creatures/

Szekely, P. (2018, December 30). Large Ground Finch[Photograph]. Flickr, Puerto Villamil, Galapagos, Ecuador.

Szeleky, P. (2018, December 30). Galapagos[Photograph]. Puerto Villamil, Galapagos, Ecuador.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/pedrosz/47257963311

U. (2015, December 17). Darwin's finches may face extinction. Retrieved from https://phys.org/news/2015-12-darwin-finches-extinction.html

VOLUME 24, ISSUE 9

![Galapagos Finch Szeleky, P. (2018, December 30). Galapagos [Photograph]. Puerto Villamil, Galapagos, Ecuador. https://www.flickr.com/photos/pedrosz/47257963311](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/media/image/2019-04/47257963311_d5e9318a3e_b_0.jpg?itok=MZ4hrdsm)

![Scalesia Trees, Santa Cruz, Galapagos H. (2008, August). Scalesia pedunculata [Photograph]. Santa Cruz, Galapagos. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scalesia_pedunculata.jpg](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/media/image/2019-04/Scalesia_pedunculata.jpg?itok=VYNwBPFW)